- Home /

- Local areas /

- Gippsland Lakes

Overview

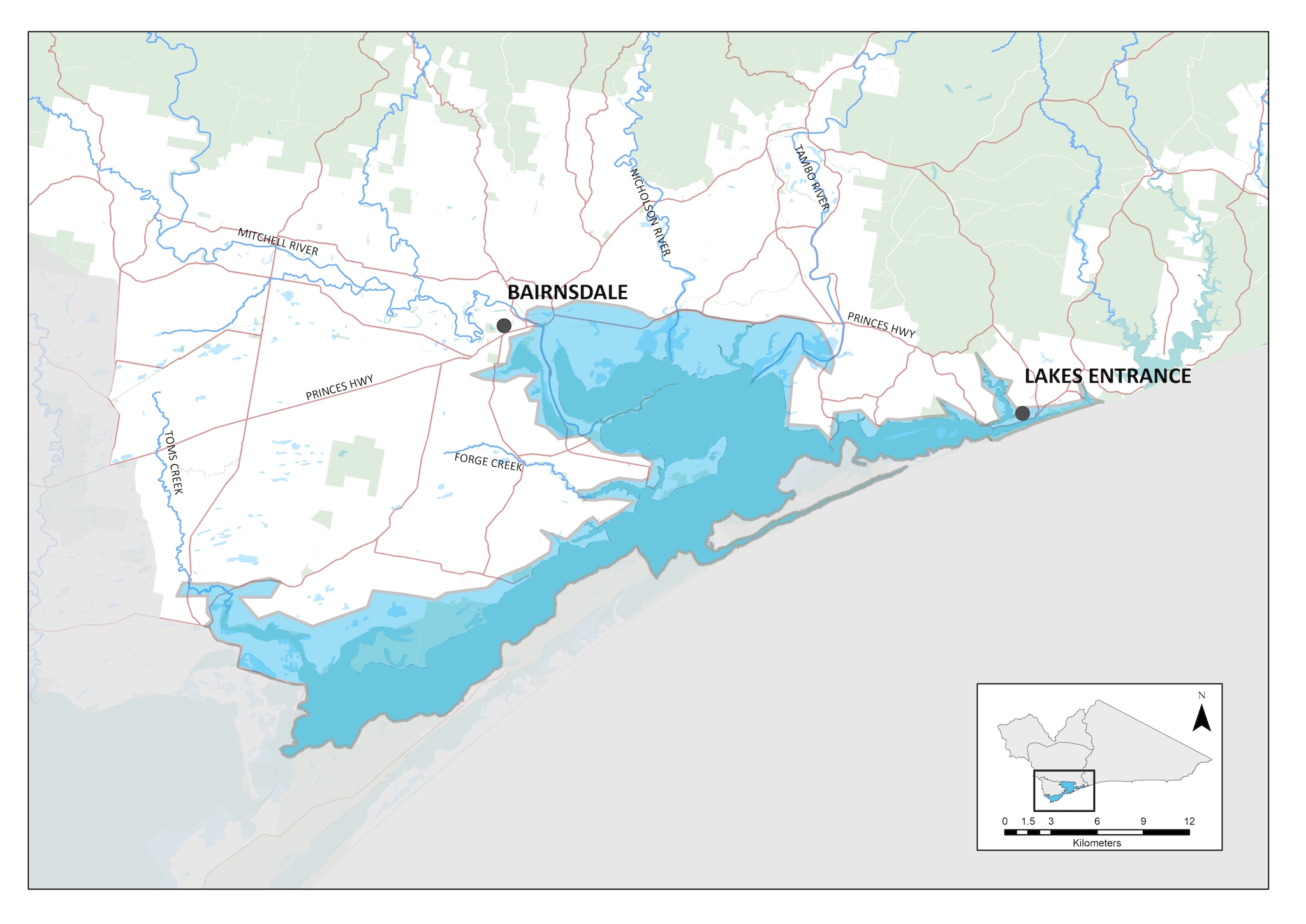

The Gippsland Lakes form a large estuarine system, which extends between Sale in the west and Lakes Entrance in the east. The lake system is listed under the Ramsar Convention as a wetland of international importance. The lakes support substantial numbers of waterbirds, often during critical life stages and through drought. They also support a range of threatened flora and fauna and are an important site for fish populations. The lakes neighbour the urban centres of Bairnsdale, Lakes Entrance and Paynesville and are highly valued for recreational pursuits such as boating and fishing that help support the economy of the Gippsland region.

Only a portion of the Gippsland Lakes lies within the East Gippsland CMA region. This equates largely to Lakes Victoria, and King (including Jones Bay) and associated fringing wetland areas, including the freshwater wetland of MacLeod Morass. While East Gippsland CMA will continue to work collaboratively with West Gippsland CMA to manage the Gippsland Lakes, this local area paper is focussed on the portion of the Gippsland Lakes that is within the East Gippsland CMA region.

Recent assessments have indicated that the Gippsland Lakes and adjoining areas are generally in fair to good condition (Table 1). The site remains recognised as a Wetland of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention, and the values leading to that listing (coastal saltmarsh, waterbirds, native fish) all continue to be maintained by the site.

The main lakes and the fringing wetlands are a system in transition that has been occurring for over 100 years. The arrival of Europeans has seen changes in land use in the catchment and the establishment of towns and urban development around the Lakes. Into the future change is likely to increase with an increasing population and climate change predicted to alter the system further. The Gippsland Lakes will continue to adapt to the changing conditions, and, with efforts, key values can be maintained, and new values are likely to emerge.

Table 1: Condition and trend of the Gippsland Lakes

| Theme | Indicator | Data Source | Condition | Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | Water resource use | Asutralian Bureau of Meteorology (2021) | Surface and groundwater extraction is relatively low and connectivity between the rivers, lakes and the sea remain relatively unimpeded. | Stable |

| Freshwater wetland habitat | Gippsland Lakes Environment Report (EGCMA, 2021) | A habitat mosaic of open water, emergent reed beds and paperbark is being maintained at Macleod Morass, one of the few freshwater wetlands in the region. | Unknown | |

| Coasts and marine | Water quality | Gippsland Lakes Environment Report (EGCMA, 2021) | Water quality is highly variable over short time scales, but largely stable in Lakes Victoria and King over longer time periods. In years of high rainfall, large loads of nutrients can enter the Lakes resulting in algal blooms, which may temporarily impact on values. While there is some evidence of increasing in salinity in the west of the Gippsland Lakes, water quality in Lakes King and Victoria is fair to good. | Stable |

| Estuary condition | Index of Estuary Condition (DELWP 2021) | The estuaries of the Mitchell, Tambo and Nicholson Rivers are in good to moderate condition. | Unknown | |

| Vegetation extent and condition | Gippsland Lakes Environment Report (EGCMA, 2021) | Seagrass and saltmarsh extent and condition is being maintained. | Stable | |

| Biodiversity | Fish diversity and abundance | Victorian Fisheries Authority 2019 assessment; Gippsland Lakes Environment Report (EGCMA, 2021) | The lakes support over 100 species of native fish including freshwater, estuarine and marine opportunist species. While there have been declines in some commercial fish species such as black bream, other species such as silver trevally are considered stable. | Potentially declining |

| Key species | Gippsland Lakes Environment Report (EGCMA, 2021) | Waterbird abundance and diversity is considered indicative of good condition, with > 20,000 waterbirds supported annually and over 90 species detected in the past five years. | Stable | |

| There have been impacts to populations of Burrunan dolphins in 2021, which now can be considered in fair condition. | Unknown | |||

| The Gippsland Lakes support at least 96 threatened species, three of which have > 50% of their Victorian range in this local area. | Unknown | |||

| Community | Landcare group health score | Landcare Group Health Survey (2015 -2020) | Participation in Landcare activities has continued around the Gippsland Lakes with the group health score remaining moderately high. | Stable |

| Population | Australian Bureau of Statistics (2020) | Around 70% of the population of the East Gippsland region lives around the Gippsland Lakes and these areas contain the fastest growing populations in East Gippsland. In In Paynesville, for example, there has been a 50% increase in population since 2001.. | Increasing |

The following major threats to the Gippsland Lakes are identified in the Gippsland Lakes Ramsar Site Management Plan and stakeholder workshops.

Nutrient and sediment inflows

Increased nutrient and sediment loads from the catchment have been identified as significant drivers of water quality decline in the Lakes, leading to algal blooms and impacts to ecological, economic and social values. Riverine nutrient loads are generally the greatest source of nutrients to the system. Events such as bushfires in the catchment, result in the mobilisation of large amounts of sediment and nutrients into the system. Increased algal blooms and sediments can directly impact seagrass extent, which in turn results in reduced habitat for native fish and birds. Algal blooms also have a direct impact on recreation and tourism in the system.

Pest plants and animals

There are broad range of pest plants and animals that are impacting the habitats and communities of the Gippsland Lakes. Introduced predators such as foxes and cats have a direct impact on waterbirds, including shorebirds and beach nesting species such as the threatened little tern and fairy tern. Large herbivores, particularly deer and grazing stock are common in the fringing wetlands and can cause significant damage to wetland vegetation communities. Other herbivores such as rabbits and goats have caused localised damage to wetland habitats and introduced marine pests represent a risk to sensitive aquatic ecosystems, particularly in Lake King.

Climate change

The climate has already changed and is continuing to change at an accelerated rate. Increased temperatures, decreased rainfall and rising sea levels are having a profound effect on the Gippsland Lakes. Increasing salinity, increased inundation of intertidal communities and potential salinisation of freshwater wetlands are all serious risks to the values of the Gippsland Lakes. There are also predictions of increased fire and flood events, which could lead to more frequent inflows of nutrients and sediments to the system, further impacting aquatic communities.

Recreation

The Gippsland Lakes support significant recreational activities including boating, fishing and camping. Recreational pressure is growing as populations in Victoria and beyond grow and increased tourists visit the Gippsland Lakes. Vehicle damage to saltmarsh from four-wheel drives and trail bikes has been reported for areas around Jones Bay. Saltmarsh is slow to recover from damage, which not only impacts this EPBC listed threatened ecological community, but also the biota such as shorebirds which rely on this important foraging habitat. Disturbance by humans, domestic dogs and recreation activities represent a significant risk to shorebirds, which need to spend a large portion of their time building up reserves to make the long journey back to the northern hemisphere. Studies have shown that disturbance when roosting or feeding may result in a significant loss of energy and compromise their survival. In addition, many beach nesting birds are susceptible to inadvertent destruction of eggs, or nest abandonment by recreational activities. The popularity of the lakes for boating can impact on habitats such as seagrass communities which can be damaged from moorings and Burrunan dolphins, which alter their behaviour to avoid busy boating areas.

Decreased freshwater inflows

Approximately 20% of the total average freshwater inflow to the Gippsland Lakes is extracted for a number of consumptive purposes. While, the majority of extraction occurs from the Western Rivers, there are extractions from the Mitchell and Tambo Rivers that decrease end of system flows into the eastern portion of the Gippsland Lakes. It is likely that increased extraction from the western rivers could influence future salinity regimes in Lakes King and Victoria. Many of the values of the eastern Lakes such as estuarine fish (e.g. black bream), Burrunan dolphin and seagrass are dependent on maintained salinity regimes.

Vision

To maintain, and where necessary improve, the ecological character of the Gippsland Lakes Ramsar Site and promote wise use.

Outcomes

By 2040, the long term objectives for the Gippsland Lakes are to:

- implement integrated programs of work to maintain or improve the ecological health of the Gippsland Lakes focussing on fostering cooperation and coordination between agencies and organisations, and maximising outcomes through leveraging investments

- further develop and enhance the capacity of Traditional Owners to manage country, including increased opportunities to coordinate and lead natural resource management programs

- protect and enhance freshwater habitat, focussing on critical habitat types for freshwater dependant species

- assist in the adaptation of vulnerable landscapes to the impacts of climate change

- maintain condition, and improve the extent, of fringing habitats including variably saline wetlands and saltmarsh

- maintain and better understand aquatic vegetation communities and species critical to the ecological character of the Gippsland Lakes.

This will be achieved by focussing on the following themes:

- Coasts and marine – improving vegetation in fringing wetlands and shorelines of Lakes King and Victoria

- Water – managing salinity, nutrients and sediments

- Biodiversity – improving aquatic habitats and ecosystems, including freshwater wetlands

- Community – promoting awareness of, and participation by, communities in the management of the lakes.

Progress under each of these themes will be achieved by working with local communities and Traditional Owners to build awareness and understanding of the overall system, and by working together to manage the lakes. There is also a focus on coordination and cooperation between the many agencies and organisations with an interest in the lakes. This coordination and cooperation aims to maximise outcomes through leveraging investments.

Coasts and marine – improving the fringing wetlands and shorelines of Jones Bay and Lake King

Current State

(2021)

The shorelines of Lakes Victoria and King (including Jones Bay) support a mosaic of saltmarsh, emergent reeds (e.g. common reed) and swamp scrub (paperbark). Condition assessments of saltmarsh in 2019 indicated 24% of sites in poor condition, 40% in fair condition and 36% in good condition. Recreational vehicles, domestic stock and large herbivores have been identified as significant threats.

Medium-term

Outcomes (2027)

Control of domestic stock and recreational vehicle access is in place across 25% of priority saltmarsh areas.

Increased areas of permanent protection in saltmarsh communities.

Long-term

Outcomes (2040)

The extent of saltmarsh and swamp scrub communities is maintained, and condition of poor and fair saltmarsh communities is improved.

Water – managing salinity, nutrients and sediments

Current State

(2021)

Loads of nutrients entering the system are largely a result of western river inflows, although the Mitchell River (and to a lesser extent, the Nicholson/ Tambo, contribute loads of nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment to Lake King. Algal blooms are a current feature of the system.

MacLeod Morass is the only significant, public freshwater wetland in the system. The salinity and nutrient regimes of this system remain a knowledge gap.

Medium-term

Outcomes (2027)

Works have been completed in 30% of priority reaches and sub-catchments to reduce sediment input to waterways flowing to the Gippsland Lakes.

A reduction in the number of years in which blue-green algal blooms occur in the lakes to less than five over the 20 years (2007–2027).

Water regimes in MacLeod Morass are managed to maintain freshwater conditions in the upper Morass as indicated by annual average EC of < 500

Long-term

Outcomes (2040)

Extent and condition (density) of seagrass is maintained.

Macleod Morass is maintained as a freshwater wetland.

Biodiversity – improving aquatic habitats and ecosystems

Current State

(2021)

The freshwater, estuarine and coastal lagoon habitats of the Gippsland Lakes support a diversity of flora and fauna. This includes several threatened species such as EPBC listed waterbirds and, EPBC listed green and golden bell frog and the Victorian listed Burrunan dolphin. While the status of threatened waterbird and frog populations remain a knowledge gap, there is some evidence that there have been recent impacts to Burrunan dolphin populations.

Pest plants and animals together with increased recreation have been identified as key threats to the fauna of the Gippsland Lakes.

Medium-term

Outcomes (2027)

Sustained predator control has been implemented in 60% of known priority waterbird foraging and breeding sites.

Control of large herbivores in 30% priority wetlands where impacts have been observed and measured.

No new sustained marine pest infestations in the Gippsland Lakes have occurred.

The drivers of Burrunan dolphin population dynamics will be well understood.

Long-term

Outcomes (2040)

Diversity and abundance of waterbirds are maintained at priority locations around the Lakes.

Diversity of fish is maintained in Lakes Victoria and King.

Populations of Burrunan dolphins are stable.

Community – promoting awareness of, and participation in, management of the lakes

Current State

(2021)

The broader community are currently informed and engaged through the Love Our Lakes platform including a dedicated website, social media profiles and targeted traditional media and events.

Community groups are able to participate in the management and improvement of the lakes environment through volunteer and community grants programs.

Medium-term

Outcomes (2027)

Gippsland Lakes communities will continue to have a single point of reference of the most up to date condition and on ground program delivery information for the Gippsland Lakes.

Local community driven groups will be focused on achieving the long-term objectives for the lakes and maximizing opportunities to align and collaborate with Traditional Owners, and land and waterway managers.

Regular opportunities to implement community priority project will be provided.

Long-term

Outcomes (2040)

Gippsland Lakes communities are well informed about the condition and threats to the biodiversity and habitats of the lakes.

Community priorities are well integrated into the broader implementation of programs of works to improve the health of the Gippsland Lakes.

Active citizen science programs will help inform the long-term monitoring of ecological condition of the Gippsland Lakes.

On-ground projects continue to be delivered in priority areas across the lakes.

With respect to the delivery of actions outlined in each of the Local Areas covered by this RCS, there are four phases in the implementation framework:

- Target setting – A vision is set for each local area, including outcomes, aiming for the healthiest environment tailored to community and Traditional Owner aspirations and regional characteristics. Actions are developed in collaboration with partner agencies, targeting threats to the Local Area

- Taking action – Land managers and community work intensively to maintain and improve our natural environments. Examples of work undertaken during this phase include pest plant and animal control, revegetation, and hosting engagement events. This phase is working together to achieve results on the ground

- Recovery and growth – Once the delivery of on ground works is complete, the local area (and the life within it) will take some time to recover and establish. In some cases, environmental works will cause a minor decline before the environment can find its balance and improve in condition. This phase provides for on ground works to be delivered at a level for the environment to establish into a stronger, more resilient, and healthier Local Area.

- Target achieved – The Local Area is resilient, providing community values and is largely naturally sustained. Threats to the local area are now reduced (along with the costs to fix them). The environment is stronger, more resistant, and resilient to threats. The local area will need minimal maintenance, although ongoing monitoring may be required, and the outcomes have been achieved

These phases describe the current status and trajectory of the local area. Different places across a single Local Area may be in different phases of the implementation framework. A range of catchment and wetland protection and restoration works have been underway in the Gippsland Lakes since the 1990s, with the site still largely in the Taking Action phase transitioning to the Recovery and Growth phase. By contrast, activities addressing knowledge and information gaps in the coastal and marine areas of the site are still in the Target Setting phase.

- Develop a staged program for works and activities in line with Gippsland Lakes Priorities Plan, Gippsland Lakes Ramsar Site Management Plan, East Gippsland Waterway Strategy, Biodiversity Response Planning process (Gippsland Lakes Focus Landscape), the Gunaikurnai and Victorian Government Joint Management Plan, the Trust for Nature Statewide Conservation Plan, and the Gippsland Plains and Strzelecki Ranges Conservation Action Plan.

- Build understanding of Traditional Owner knowledge and how to incorporate this into management and maintenance of the lakes.

- Further develop and broaden the education and awareness campaign around the lakes.

- Carry out priority investigations, for example:

- climate change impacts

- ecological impacts of algal bloom

- effects of altered salinity on the Burrunan dolphin.

- Continue to implement the strategies of the Gippsland Lakes Ramsar Site Management Plan (including an update to the RSMP in 2023).

- Drawing on spatial decision-support tools such as Strategic Management Prospects, implement in priority areas consistent with the Biodiversity Response Planning process (for relevant Landscapes):

- sustained weed control, integrated predator control, large herbivore control, and revegetation (Gippsland Lakes Focus Landscape).

- permanent protection on private land (Gippsland Lakes Focus Landscape – particularly for Coastal Saltmarsh, riparian and wetland areas).

- Control domestic stock and recreational vehicle access in saltmarsh communities around the lakes.

- Work with Agriculture Victoria, DELWP, Parks Victoria and other partners to prioritise and manage invasive marine pests in Lake King.

- Identify and action conservation covenants as detailed in the Trust for Nature (2013) Statewide Conservation Plan for Private Land in Victoria.

- Continue to work with Traditional Owners to understand and share knowledge to protect and enhance Country and cultural sites of significance.

- Support activities for improving integrated water management as specified in the East Gippsland Integrated Water Management Strategic Directions Statement.

- Providing support to Traditional Owners to realise the goals of the Joint Management Plans, including enabling self-determination in priority setting, project involvement and project delivery more broadly across the Gippsland Lakes.

- Participate in adaptation planning and emergency management activities related to bushfire and flood impacts on the Gippsland Lakes environment.

- Monitor and manage threats from invasive plants and predators.

- Continue to work with public and private land managers to maintain past work sites.

- Monitor flora and fauna populations, including threatened species.

- Monitor and maintain works following flood or fire.

- Maintain support for public and private land managers (e.g. expert advice, access to grants for enhancement works).

- Maintain the ecological condition from recent investment, such as weed control to support natural processes.

- Conduct systematic monitoring of key factors for maintaining site health e.g. water quality (nutrients and sediments), waterbird numbers, fish and marine mammal numbers and invasive species.

- Evaluate project achievements against aims and objectives.