- Home /

- This Region

Regional Overview

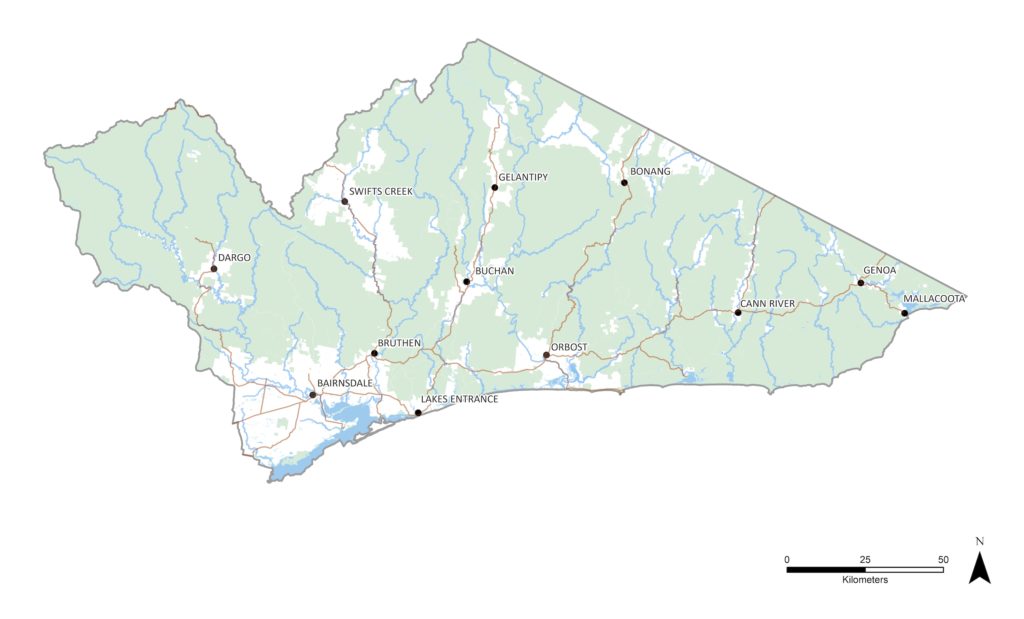

The East Gippsland Catchment Management region covers 2.2 million hectares of land, lakes and coastal waters in eastern Victoria.

About 83% of the region is in public ownership, mainly as state forests, national and coastal parks, and marine national parks, and virtually all of this retains extensive native vegetation cover.

East Gippsland is the only place on mainland Australia where such continuity of natural ecosystems – from the alps to the sea – still exists.

Located entirely south of the Great Dividing Range the East Gippsland region includes the catchments of streams from the Mitchell River eastwards to the Victoria–New South Wales border.

The northern boundary is formed by the Great Dividing Range where mountains rise to elevations of 1500 metres. The southern boundary is located three nautical miles (5.5 km) off the coast.

Rivers generally run from north to south, rising in the alpine reaches and progressing through lowland forests to coastal estuaries in the south.

The region contains significant natural assets like the declared ‘heritage rivers’ of the Mitchell, Snowy, Bemm and Genoa River catchments, the Ramsar listed wetlands of the Gippsland Lakes, and many national parks and reserves, stretching from sub-alpine environments to the coast.

Private land covers 17% of the region. Grazing occupies the largest area, and there are significant productive areas of irrigated horticulture and dairying on the floodplains of the Snowy and Mitchell rivers.

Variability in rainfall across the region gives rise to droughts and floods that have an effect on waterway health, fire frequency and intensity, and land management. This variability is likely to further increase under the influence of climate change.

The influence of climate change on the natural environments and resources of East Gippsland likely poses the greatest threat to key values into the future. The impacts of a changing climate will impact our water resources, our costal environments, important species and vegetation communities, the way we can use our land, and the resilience of our communities. Other threats including pest plant and animals in our landscape, and extreme events like drought, flood, and bushfire will potentially compound these impacts.

Our region includes most of the East Gippsland Shire, the northern part of the Wellington Shire, and part of the Alpine Shire south of the Great Dividing Range. It abuts the Wangaratta Shire in the north-east and the New South Wales shires of Snowy Valleys, Snowy Monero and Bega Valley. The East Gippsland CMA boundary also adjoins that of the West Gippsland, North East and Goulburn Broken CMA’s.

Working in partnership is a key approach within East Gippsland and ‘cross border’ relationships form an important part of the management of natural resources within our region. This approach recognises the ability of values and threats to move across administrative boundaries, and that the most effective way to manage this is through shared outcomes and a shared vision delivered in partnership.

Examples of these partnerships include working with the West Gippsland CMA in the management of the Gippsland Lakes Ramsar Site; collaborating with the NSW government on water and environmental management along the Snowy and Genoa River corridors; and working together with land managers and adjoining CMA’s to protect key values across the Victorian alps.

In 2016, the East Gippsland local government area had a population of 48,376 people (East Gippsland Shire Council).

Aboriginal people have a strong connection to country in East Gippsland and are represented by the Gunaikurnai, Bidwell, and Ngarigo Monero people.

Aboriginal people have an aspiration to participate in the management of the region’s natural resources, and this aspiration is acknowledged by natural resource management agencies across the region.

The major population centre across East Gippsland include Bairnsdale, Lakes Entrance, Paynesville, Orbost and Mallacoota. There are many smaller towns such as Bruthen, Cann River, Dargo, Ensay and Swifts Creek, with some situated in remote locations.

Increases in population over recent years has not been evenly distributed across the region. Large centres such as Bairnsdale and the coastal communities in the west of the region continue to support more residents than the far east

Current economic profiling for the East Gippsland Shire shows that the major industries by output are manufacturing, construction, agriculture, forestry and fishery, renting, hiring and real estate services, health care and social assistance, accommodation and food services, and retail trade.

In 2016, the value of agricultural commodities for East Gippsland was $240 million annually, consisting of crops, livestock and livestock products (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020).

Victoria’s largest offshore commercial fishing fleet is based at Lakes Entrance. The port handles about 10,000 tonnes of seafood annually with a landed value of $30 million

The tourism industry attracted 1.2 million visitors in 2018, contributing $340 million to the regional economy. Major tourist destinations are Lakes Entrance, Metung and Paynesville on the Gippsland Lakes, and Mallacoota in the east. Nature based tourism is an important component of the total tourism industry.

More information on the economic and industry profile of the East Gippsland Shire can be found on the Shire website > Economic Development.

The communities of East Gippsland are resilient. The past years have been some of the most challenging our community have faced. An extended period of drought followed by widespread bushfires and the impacts of the Coronavirus pandemic have impacted on the health and well-being of many people and communities across the region. Impacts of the experiences of recent years have been significant, and communities are concerned about the challenges we may face into the future.

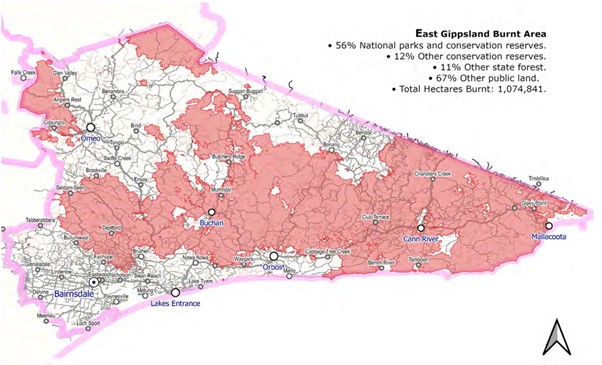

On 21 November 2019 lightning strikes ignited numerous fires in East Gippsland, with the region experiencing significant drought and severe, widespread dryness in the region.

Unfavourable conditions and remote locations meant the fires were difficult to contain and several fires joined, creating fires of a magnitude previously unseen in Gippsland, the Victoria’s North East and adjacent NSW.

In late December, dry lightning started new fires west of Mallacoota and these merged on New Year’s Eve during extreme fire and weather conditions.

Over 56% of the East Gippsland region was within the fire impact footprint.

With three fatalities, over 450 residences and commercial properties destroyed or damaged, the immediate loss from the event was significant for the East Gippsland community.

46,000 residents and 118 communities were directly or indirectly impacted, and an estimated loss of visitor expenditure for Gippsland of $170-180 million placed further pressure on impacted communities. A range of bushfire recovery programs have been implemented collaboratively across the region following the fires. More information can be found on bushfire recovery planning and reporting coordinated by the East Gippsland Shire Council and the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action

Impacts of bushfires on biodiversity

The fires across Victoria burnt mostly in areas that have high biodiversity value. There were 244 species with more than 50 per cent of their modelled habitat within the burnt area, including 215 Victorian rare or threatened species. This includes four species listed under the Commonwealth EPBC Act 1999.

The fire extent impacted at least 60 per cent of over 75 National parks and nature conservation reserves in Victoria.

78 per cent of the Warm Temperate Rainforest is within the fire extent, and the majority of the distribution of seven vegetation communities listed under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (FFG Act) are also within the burnt area.

A significant area of habitat across Victoria has now burnt multiple times since 2000. This can result in regeneration failure for Alpine Ash.

Across East Gippsland areas impacted included:

- 56% of National parks and conservation reserves

- 53% Water-supply catchments; and

- 32,046 ha of waterways and riparian areas.

Large areas of Rainforest (32% of Cool temperate rainforest; and 77% of Warm and dry temperate rainforest) were affected by the fires.

Species and vegetation communities of most immediate concern include the Long-footed Potoroo, Ground Parrot, Glossy Black-cockatoo, Large Brown Tree Frog, Diamond Python, Freshwater Galaxiids, Colquhoun Grevillea, Betka Bottlebrush and Warm Temperate Rainforest.

Some species, such as the Brush-tailed Rock-wallaby and the Guthega Skink, were not as impacted as first predicted, as the fire did not reach key populations. Other species appear to be showing some resilience to the fires, such as Yellow-bellied Water Skink

Impacts of bushfires on water quantity

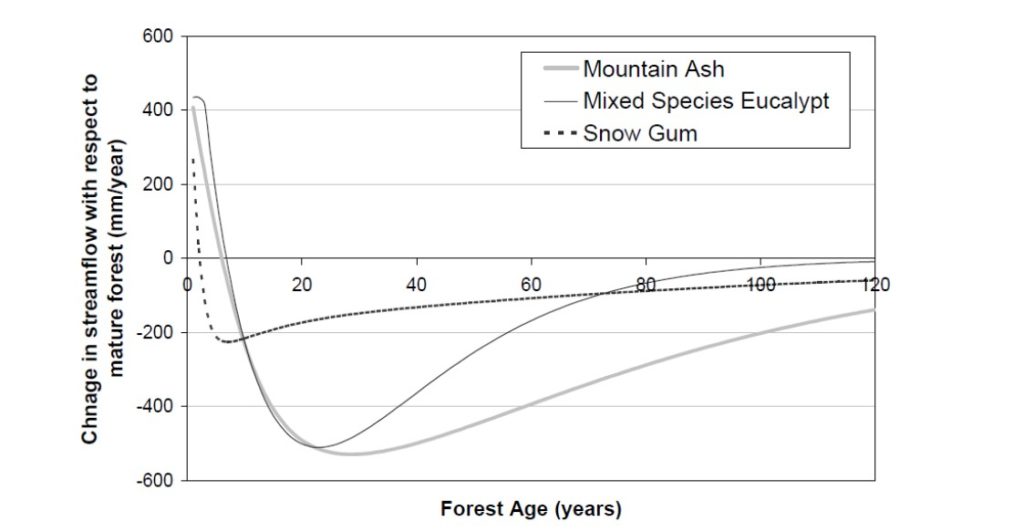

Immediately following a bushfire, streamflows typically increase due to increased runoff from bare surfaces. The loss of forest canopy and ground cover means less interception of rainfall as well as less water-use by the forest as a whole (less “evapotranspiration”), meaning more runoff to streams. This increase in streamflows lasts until the forest vegetation recovers or regrows (5-10 years, or less for partial burns).

As the forest regenerates, vigorous growth and re-growth increases evapotranspiration above pre-fire conditions, so streamflows decrease below what would be expected without fire. This reduction reaches a maximum at 20-30 years post-fire then slowly recovers as the forest ages (in the absence of any other further disturbances).

Figure 3 shows this graphically as a worst case for “complete burn”. It plots years since fire versus runoff relative to pre-fire conditions. It illustrates that different types of forests behave differently in the magnitude and timing of the initial streamflow increase; the subsequent reduction due to vigorous growth; and then recovery as the forest matures.

The exact shape of these curves for a real catchment depend on forest type, pre-fire age of forests, severity of burn, and the general soil and climatic conditions in the catchment. In practice, each burnt area will be a complex mosaic of forest types, ages, burn severity and catchment characteristics.

Actual impacts on streamflow of the 2019/20 fires across EGCMA catchments will depend on areas of different fire severity; but it is clear that there will be significant impacts, particularly for the far eastern rivers where a very high percentage of catchments was burnt.

Impacts of bushfires on water quality

The impacts on water quality are more obvious following fire due to the immediate visual changes within waterways. Sediment, nutrients and contaminants are mobilised because of loss of cover exposing soil, mobilisation of nutrients in soil, decaying vegetation and ash, and increased likelihood of landslips and debris flows.

The increased runoff immediately following fires exacerbates these problems.

Consequences for our waterways include:

- smothering of in-stream plants and animals,

- reduction of in-stream dissolved oxygen levels,

- eutrophication (over-load of nutrients), and

- coarse sediment slugs and pulses.

Impacts experienced immediately after the fires are generally the most significant, and declining as forest cover is re-established, but some impacts continue for many years and will be exacerbated by multiple burns. The effects of multiple burns can be readily seen after each rain event.

Sediment deposited on banks after initial rainfall can be re-entrained during large runoff events, coarse sediment on the bed moves slowly through the systems, reducing the diversity of “pools and riffles” (that are important aquatic habitat), and the nutrients built up in deposited material can release back into receiving waters. For example algal blooms in the Gippsland Lakes can be exacerbated by large stores of nutrients in sediment, released due to particular climatic conditions.

Following the 2019/20 bushfires, the EPA undertook monitoring at sites deemed “of high recreational use” with the intention of indicating risks to activities such as swimming and fishing. The data shows obvious impacts of landscape fires on water quality, especially after localised rain events. Data from these and other sites are available in real-time from: http://data.water.vic.gov.au/postbushfireswq

Management implications

Work has been undertaken over the last 15 years to understand options for mitigating the effects of bushfires on water quality. The following summarises the current options available, and whilst they were developed with a focus on the Gippsland Lakes, they are generally applicable to catchments across East Gippsland:

- Undertake prescribed burning using procedures that will protect water quality – Water quality impacts are related to fire intensity, so well managed prescribed burns have the potential to reduce water quality impacts of subsequent wild-fires, especially if riparian areas can be protected. Note there is also a risk that prescribed burns can themselves cause water quality problems if not managed well.

- Undertake rehabilitation activities as part of fire suppression – Often fire breaks and tracks are constructed in haste as part of the fire fighting effort. Rehabilitation of these works should take place as soon as the immediate fire danger is over (i.e. within a one to a few days of their construction), rather than waiting until the fire is extinguished, or until the end of the fire season.

- Identify those areas that contribute high nutrient loads to the lakes and that are cost effective to mitigate. These might include eroding areas that are hydrologically well connected to waterways.

Ideally, consideration of water quality impacts would be incorporated into all fire suppression practices. Additionally, the impacts of major fires cannot be fully mitigated through the delivery of existing waterway health improvement programs alone, and preventative solutions must be found to reduce or mitigate longer term declines in waterway health