The ‘coast and marine theme’ of this Regional Catchment Strategy includes the estuaries and coastal environments of East Gippsland, including the offshore ocean environments. Our coasts are highly valued by our community and provide some of the last remaining truly wild places in Victoria.

Our coastal and marine values… a snapshot

The coastal and marine environments of East Gippsland support significant ecological, social and economic values.

Our coast supports plants and animals including nationally listed threatened ecological communities, visiting international migratory shorebirds, and diverse and unique populations of marine mammals, fish and invertebrates and part of the Gippsland Lakes Ramsar Site.

East Gippsland’s coastal economy is based largely on natural resources. Coastal dependent economic sectors include oil and gas in Bass Strait, fisheries, commercial ports, shipping, commercial boating and services supported by coastal settlements and tourism. The scenic beauty and recreational amenity of our coasts are valued by residents and tourists, with boating and recreational fishing popular activities that make significant contributions to the local economy.

The coast and marine environment of East Gippsland support significant ecological values including nationally listed threatened ecological communities such as temperate coastal saltmarsh and littoral rainforest (listed under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act); international migratory shorebirds which feed in the soft sediments of the lakes, estuaries and intertidal zones, marine mammals including one of only two resident populations of the Burrunan dolphin and a diversity of fish and invertebrate species.

East Gippsland includes Lakes Victoria, King and Tyers which are all part of the Gippsland Lakes Ramsar Site. The Ramsar site supports extensive seagrass beds, important areas of coastal saltmarsh, over 80 species of waterbird and an abundance of fish. Some species migrate from fresh to marine waters to complete their lifecycles. Estuarine resident species and marine opportunists use the productive feeding grounds of the Gippsland Lakes coastal lagoons.

The marine habitats of East Gippsland, including marine national parks and sanctuaries, support a wide range of aquatic habitats. Intertidal soft sediments that are feeding grounds for shorebirds, many of which migrate over 10,000 kilometres from the northern hemisphere to feed here in our spring and summer, before making the return journey. Rocky reefs dotted along the coast support diverse fish and invertebrate communities, including commercially important species. Subtidal habitats support seagrass and macroalgae beds, including stands of bull kelp.

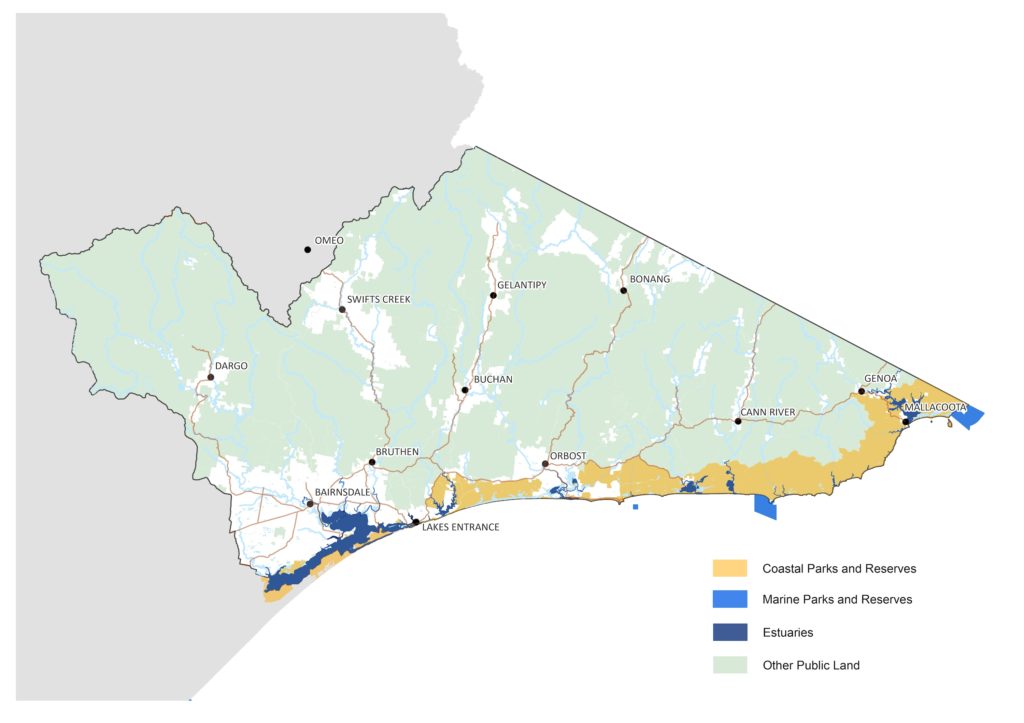

Figure 1: Marine and coastal parks of East Gippsland

Deeper waters are important feeding grounds for pelagic bird species including the nationally vulnerable shy albatross and wandering albatross. Threatened southern right whales, humpback whales, southern elephant seals and New Zealand fur seals are all found in the marine waters of East Gippsland. There are also several important haul-out sites for Australian fur seals in the region.

The sandy beaches of our region support beach nesting birds such as plovers, terns and oystercatchers. In particular, the nationally threatened little tern, fairy tern, and hooded plover have significant breeding areas in the coasts of East Gippsland. Our estuaries are important habitat for many species of native fish including the recreationally important estuary perch and black bream.

East Gippsland’s coastal economy is based largely on natural resources. Coastal dependent economic sectors include oil and gas in Bass Strait, fisheries, commercial ports, shipping, commercial boating and services supported by coastal settlements and tourism. The Gippsland coastal region is an important centre for commercial and recreational fisheries with large commercial fishing fleets operating out of Lakes Entrance. Together with the eastern zone abalone fishery based at Mallacoota, Gippsland’s estimated annual commercial catch contributes significantly to the Victorian economy.

The scenic beauty and recreational amenity of the coasts of East Gippsland are valued by residents and tourists. Coastal settlements in East Gippsland range from towns such as Lakes Entrance and Mallacoota to villages such as Bemm River and Gipsy Point. The majority of residents in coastal East Gippsland live in settlements of less than 500 people. Boating and recreational fishing are important and popular activities in East Gippsland and make significant contributions to the local economy.

Threats to coastal and marine ecosystems of East Gippsland come from local and broad scale sources. Climate change, including increased carbon dioxide, increased temperature, ocean acidification, sea level rise, increased frequency and intensity of storms, increased frequency and intensity of droughts all have the potential to impact the coastal and marine ecosystems of East Gippsland. The coastline of East Gippsland is susceptible to erosion, with only a small fraction of the coastline consisting of rocky shorelines that are resistant to this impact. The combined actions of storm surges, high tides and sea level rise not only result in coastal flooding but accelerate coastal erosion.

Climate change

Decreased freshwater inflows and rising sea levels will impact the Gippsland Lakes, with increasing salinity across the system becoming more common. Hotter conditions will also result in increased frequency and duration of algal blooms in the Lakes. Rising sea levels also impact saltmarsh and fringing vegetation subjecting these communities to deeper water. This will be a particular problem in areas where there are barriers such as roads preventing landward migration of saltmarsh and paperbark communities.

Reduced freshwater inflows will also affect estuary openings, with more prolonged periods of closed conditions. This impact on the quality of habitat in the estuary and prevents migratory fish from moving between rivers and the sea to complete breeding cycles. Rising sea levels and increased storm surges will increase erosion pressures on shorelines impacting natural environments and built infrastructure such as boat moorings and jetties. While ocean acidification will have impacts to marine biota and reefs, particularly to animals with calcium shells such as molluscs.

Nutrient and sediment inflows from the catchments

This can be extreme following bushfires, and can lead to serious impacts to coastal lagoon and estuarine condition. Algal blooms can occur in Lakes Victoria and King in the Gippsland Lakes affecting not only the ecology of the system, but amenity values.

Invasive species and marine pests

Weeds, grazing animals, pigs, deer and marine pests all pose a threat to marine and coastal habitats. Introductions from commercial and recreational vessels can impact on marine and coastal ecosystems. For example, the invasive screw shell has been recorded within the Point Hicks Marine National Park. This New Zealand species can quickly colonise large areas of soft sediment, changing food web structure and leading to a decline in the diversity of native invertebrate species. In 2015, the invasive Northern Pacific Seastar (Asterias amurensis) was reported in the Gippsland Lakes by the community group Friends of Beware Reef. A swift management response resulted in the eradication of the species, which was not recorded for a further five years. In 2019, the species was again spotted, again prompting a swift response and monitoring program.

Damage to seagrass, reefs and marine habitats

Anchors and recreational vessels have been identified as a threat in the region, although the extent of damage is not known. Commercial and recreational fishing can result in changes in the populations of target species and poaching of abalone has been identified as a threat to marine national parks.

Disturbance of shorebirds

Impacts to feeding and beach nesting birds by vessels, people and domestic dogs is a risk. Although much of the region is sparsely populated and disturbance is comparatively low, there are a number of popular places, such as in the Gippsland Lakes and Mallacoota Inlet where this threat is more likely to occur.

Estuaries

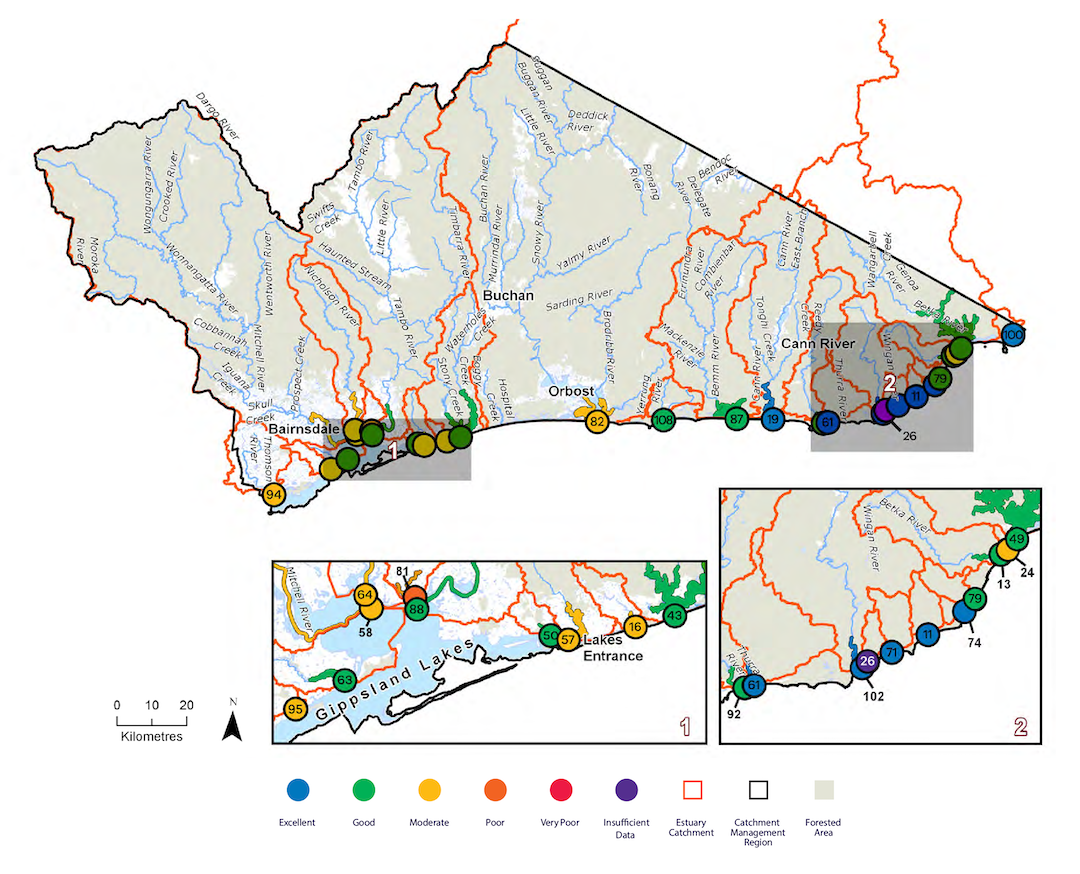

An assessment of the condition of estuaries in East Gippsland highlights the overall good condition of estuaries in the far east of the region, where the catchment is largely unmodified, development is low and native biota are supported. There are more estuaries in moderate condition as you move further west (Figure 2). The sub-indices indicate that the physical form of most of the estuaries assessed remains in good or better condition, but that many estuaries suffer from altered hydrology (Table 1). The results of these assessments must be considered in the context of recent bushfires. The assessments were completed prior to the 2019-20 bushfires, which had significant impacts on many of the catchments of the estuaries of the region.

Figure 2: Map of estuary condition in East Gippsland.

SOURCE: DELWP, 2021, Assessment of Victoria’s estuaries using the Index of Estuary Condition: Results 2021

Table 1: Index of Estuary Condition assessments for estuaries in East Gippsland (2019-20).

Excellent=Green Good=Blue Moderate=Yellow Poor=Orange Very Poor=Red

| Wetland | Physical Form | Hydrology | Water Quality | Flora | Fish | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benedore River | 10 | 10 | NA | 9 | NA | 48 |

| Betka River | 10 | 9 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 39 |

| Bunga Inlet | 9 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 28 |

| Cann River (Tamboon Inlet) | 9 | 8 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 43 |

| Davis Creek | 10 | 7 | 3 | 9 | 6 | 30 |

| Lake Tyers | 10 | 6 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 38 |

| Mallacoota Inlet | 9 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 37 |

| Maringa Creek | 10 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 36 |

| Mississippi Creek | 10 | 3 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 32 |

| Mitchell River | 9 | 5 | 9 | 5 | 9 | 32 |

| Mueller River | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 41 |

| Newlands Arm | 7 | 5 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 36 |

| Nicholson River | 8 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 30 |

| Red River | 10 | 10 | NA | 10 | NA | 50 |

| Seal Creek | 10 | 10 | NA | 10 | NA | 50 |

| Shipwreck Creek | 10 | 10 | 6 | NA | 7 | 37 |

| Slaughterhouse Creek | 10 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 24 |

| Snowy River | 9 | 1 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 31 |

| Sydenham Inlet | 9 | 6 | 10 | 5 | 8 | 34 |

| Tambo River | 8 | 5 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 34 |

| Thurra River | 10 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 6 | 39 |

| Tom Creek | 9 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 27 |

| Tom Roberts Creek | 9 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 31 |

| Wau Wauka Creek | 10 | 10 | NA | 10 | NA | 50 |

| Wingan Inlet | 10 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 41 |

| Yeerung River | 10 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 7 | 39 |

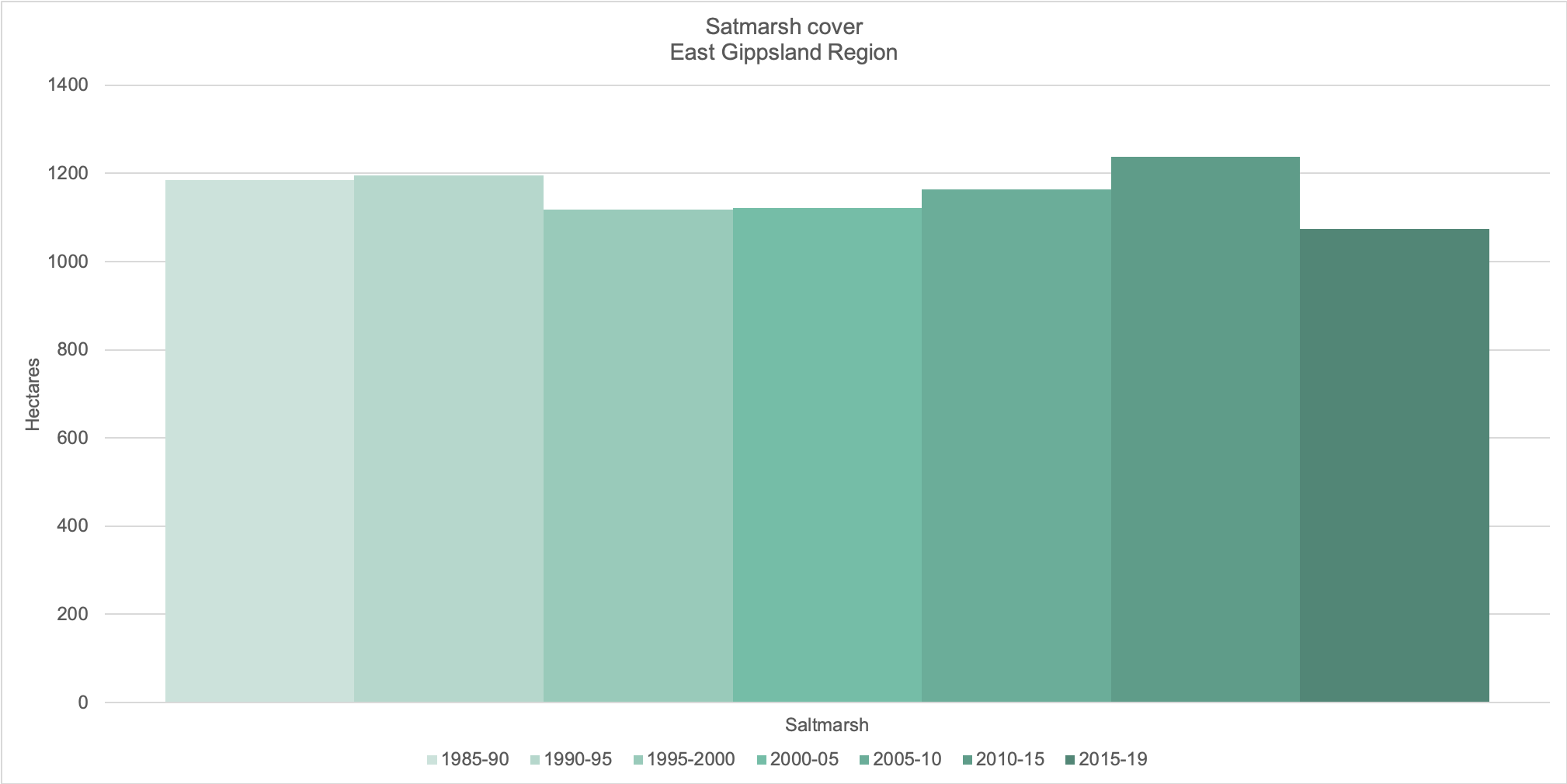

Mangroves are not a feature of the coastal habitats of East Gippsland and so the assessment of coastal vegetation is limited to saltmarsh. Saltmarsh cover in East Gippsland has declined slightly over the past five years (Figure 3). A finer scale assessment of saltmarsh in the Gippsland Lakes Ramsar site indicated that there had also been a small decline in saltmarsh from 2011 to 2020, but that ecological character of the site remained within its defined limits of acceptable change.

Figure 3: Change in extent of saltmarsh vegetation cover (hectares) in the East Gippsland Region.

Source: Victorian Land Cover Time Series (DELWP).

Water quality

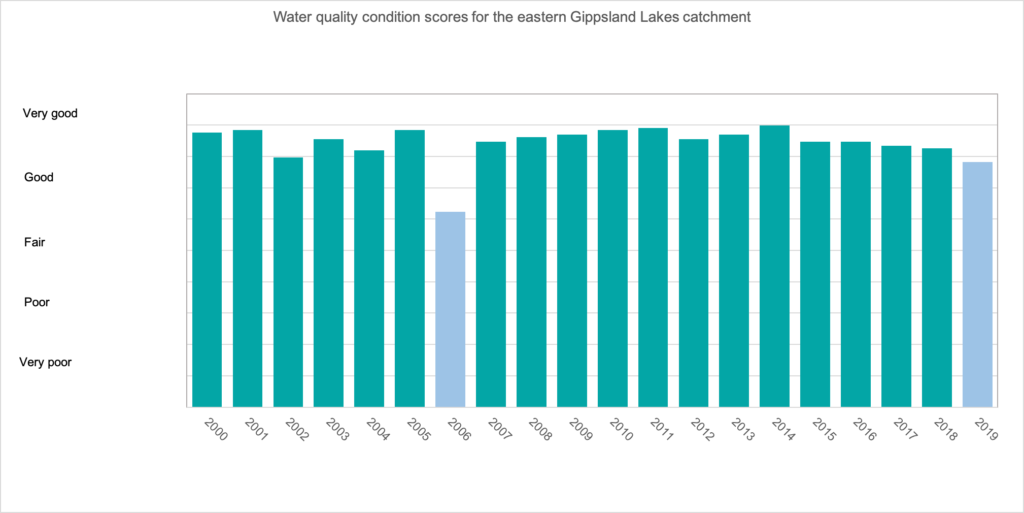

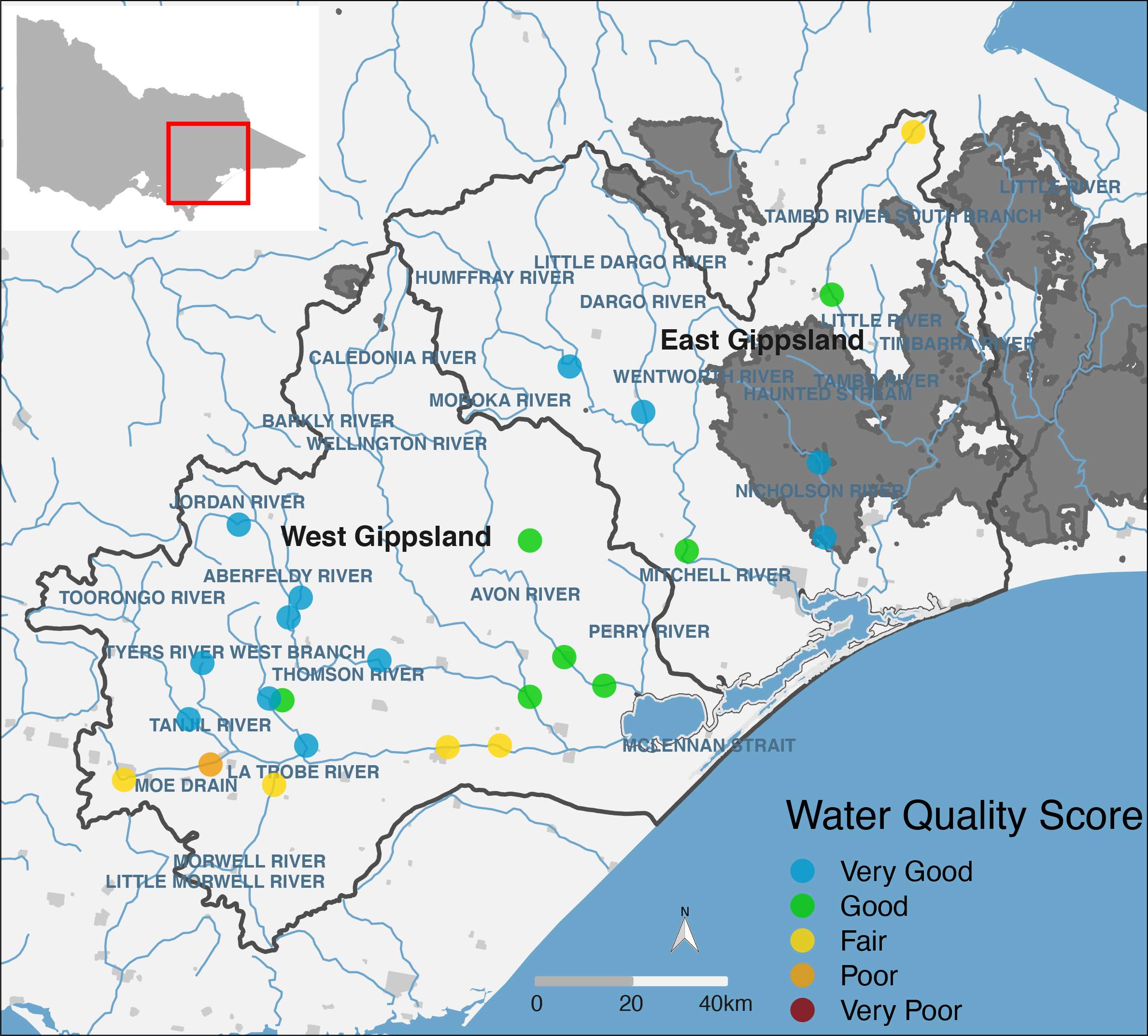

Water quality in the catchment of the Gippsland Lakes in East Gippsland has remained very good for most years in the past two decades. In 2019-20 water quality declined slightly for the first time since 2006 (Figure 4). Declines in the East Gippsland catchment were associated with poorer nutrient levels, pH and water clarity than usual. While East Gippsland experienced severe bushfires over spring/summer 2019-20, these were largely further east and impacts on water quality in the Gippsland Lakes catchments appear to have been short lived (Figure 5), although further analysis of these impacts is currently underway.

Figure 4: Water quality condition scores for the eastern Gippsland Lakes catchment.

Source EPA (2020) Publication number 1923.

Figure 5: Location and WQI scores of DELWP’s monitoring sites in the Gippsland Lakes catchment. Dark grey shaded areas show the extent of the 2019–2020 bushfires in Gippsland.

Source EPA (2020) Publication number 1923.

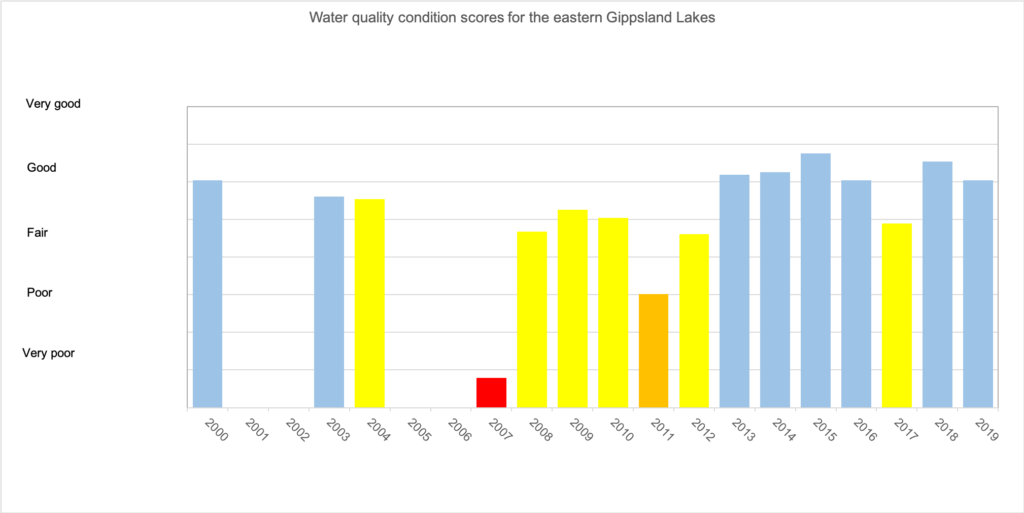

Water quality in Lakes Victoria and King has improved since the late 2000s, when condition scores were very poor to fair (Figure 6). The eastern lakes are characterised by good dissolved oxygen conditions, higher water clarity and lower nutrients and algal blooms than Lake Wellington to the west.

Figure 6: Water quality condition scores for the eastern Gippsland Lakes.

Source EPA (2020) Publication number 1923.

Coasts and Marine – Regional Outcome Targets

These regional outcomes relate to the coasts and marine theme within the RCS. They set out the long term (to 2040) and medium term (to 2027) outcomes as they relate to the region’s coastal and marine assets. The outcomes include those aligned with the statewide outcomes framework (in italics) as well regionally specific outcomes developed in collaboration with RCS partners.

The RCS outcomes framework can be found here, and more detailed outcomes addressing each theme of the RCS and linked closely to each of the local areas can be found here.

Medium-term

Outcomes (2027)

Extent of coastal saltmarsh in the Gippsland Lakes will be maintained at the average area recorded for 2005-2019 (1150 ha), enhanced by increased areas of permanent protection and improved land management.

Artificial entrance openings have been completed in line with a regionally agreed approach that appropriately considers environmental, cultural, economic and social outcomes.

A reduction in the number of years in which blue-green algal blooms occur in the Gippsland Lakes to less than five over the 20 years (2007–2027)

Sustainable sea urchin populations are maintained in all three marine protected areas in East Gippsland.

Long-term

Outcomes (2040)

Extent and condition (density) of seagrass is maintained in estuaries, including the Gippsland Lakes.

Understory species (kelp and other marine macroalgae) have been restored and sea urchin barrens are no longer visible features of the marine protected areas.

| Management Direction | Current | Future Opportunity | Partners involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working together with Traditional Owners, other regional partners and the community, set strategic directions for the identification, recovery and enhancement of marine and coastal habitats across public and private land in its catchment. | DELWP, EGCMA, GLaWAC, Parks Victoria | ||

| Continue to implement the strategies of the Gippsland Lakes Ramsar Site Management Plan (including an update to the RSMP in 2023). | EGCMA, GLaWAC, DELWP, Parks Victoria, WGCMA, DAWE, EGSC, WSC, Greening Australia, TfN, Birdlife Australia, Agriculture Victoria | ||

| Work with Agriculture Victoria, DELWP, Parks Victoria and other partners to prioritise and manage invasive marine pests in the Gippsland Lakes. | EGCMA, GLaWAC, DELWP, Parks Victoria, Agriculture Victoria | ||

| Work with Parks Victoria and other partners to manage marine National Parks, including management of urchin barrens. | DELWP, Parks Victoria | ||

| Control domestic stock and recreational vehicle access in saltmarsh communities around the Gippsland Lakes Ramsar site. | DELWP, Parks Victoria, EGCMA | ||

| Working with community and regional partners, review and continue to implement the East Gippsland Estuary Opening Protocols. | EGCMA, DELWP, Parks Victoria, EGSC, Local landholders | ||

| Support and lead the implementation of relevant activities, including facilitation of local participation, in the Marine and Coastal Strategy across East Gippsland. | DELWP, Parks Victoria, EGCMA, GLaWAC | ||

| Participate in the development and implementation of a process for the provision of coastal erosion advice for long term planning, management and adaptation for the East Gippsland coast. | DELWP, EGCMA |